Since the 1940s, Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has been the primary measure for how economies are performing. The trouble is that GDP is a blunt instrument. GDP is a composite index that tells us only how much an economy is producing – it is concerned only with growth and not the differences between good and bad growth.

As far as GDP is concerned, bad news can be good news. Operations like the oil sands can be great for GDP – not only do you get the economic benefit from all the oil that is extracted over the years, but you also get to count the clean-up and the health and environmental costs that will continue for decades to come.

More importantly, GDP is a bad measure of progress. Since 1994, GDP in Canada has increased by 31 percent, but GDP cannot tell us who has benefited, who is being left behind, or how our society is faring overall.

This is the challenge that the Canadian Index of Wellbeing (CIW) addresses in their latest report. CIW uses 64 separate indicators within eight categories – community vitality, democratic engagement, education, environment, healthy populations, leisure and culture, living standards, and time use – to measure the health of Canadian society.

Overall, the well-being of Canadians increased by 11 percent between 1994 and 2008. The problem is that this progress was not shared equally across all of society.

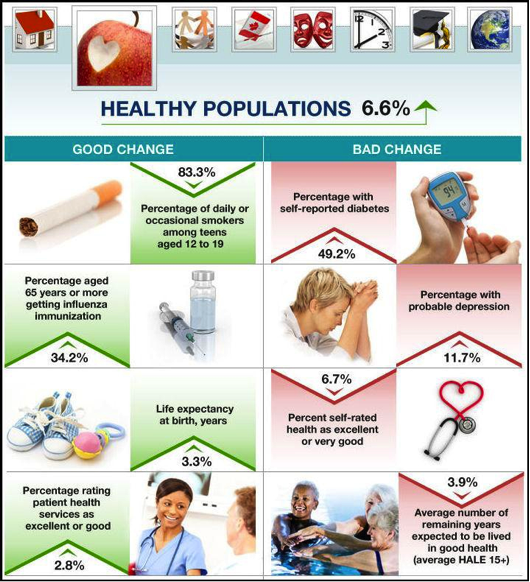

In measuring the health of our population, there was an overall increase in wellness of 6.6 percent. Life expectancy has increased, smoking rates are down, more seniors are getting flu shots, and overall access to public health services is good. However, the CIW found that health is intricately connected to income, and the income disparities between the richest 20 percent and the poorest 20 percent of Canadians has widened since 1994. This means that poor health disproportionately affects the poorest members of society.

Likewise, while overall living standards improved by 26 percent since 1994, these gains were not spread across the population. There are fewer families living in poverty and the median income of families has improved, but again, the wealthiest Canadians are enjoying the bulk of the increases to their standard of living. Not only did the income gap between rich and poor increase, but so did the gaps in economic security, employment quality and housing affordability.

Tools like the CIW are incredibly important in policy-making because they offer insights into where inequities exist within our economy and society. Simply targeting increased GDP growth as a prescription for prosperity doesn’t work. Policy makers need to take into account fairness and equality to ensure that everyone benefits from progress.