The old normal

Loneliness is in the news again. Over the COVID-19 pandemic, people have talking about feeling disconnected from others. However, it is worth remembering that being alone is a recurring topic in our modern age,5–7 famously described more than twenty years ago by Robert Putnam as a decline in society’s social capital.

A large body of research has demonstrated that social network connectedness, trust, and social participation all contribute to individuals’ well-being. Much of this work has grouped these various social factors under the term ‘social capital.’ Although social capital is a contested term, with no commonly-agreed upon definition in the academic literature, for the purposes of this blog, ‘social capital’ refers to resources available to people and society, accessed through their social relationships.

Social capital helps us find a job, keeps us healthy, and may even support a more stable and prosperous society. The literature on health has also investigated a huge range of outcomes as tied to forms of social capital, from mortality, to general self–rated health, to mental health. Therefore social capital seems like a crucial determinant of our individual and collective well-being. But it is important to remember, just as economic inequality damages other aspects of our well-being, i can also damage social capital, especially for those experiencing economic disadvantage.

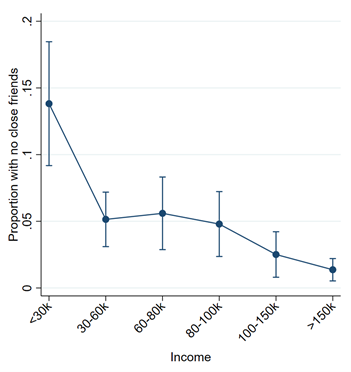

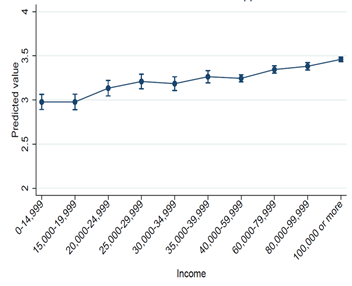

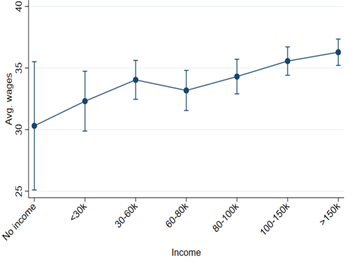

The three figures below tell the story of the ‘old normal’ for social capital in the GTA. All three use data collected just before COVID-19. In the first graph, we can see that people with the lowest income are the most likely to report having no close friends. In the second, we see that people with the highest income are also the most likely to have access to social support. In the third, we see that people with the highest income are also the most likely to have networks of people with higher income – a key form of social capital for economic and social mobility. In other words, inequality in financial capital seems to align with inequality in social capital.

Figure 1. People with the least income in the GTA are the most likely to say they have no close friends (source: Toronto Social Capital Project).

Figure 2. People with the highest income in the GTA are the most likely to say they have access to social support (source: YMCA-GTA Wellesley Monitor).

Figure 3. People with the highest income in York and Peel region are the most likely to say they have access to high-income contacts (source: York and Peel region arms of the Social Capital Project).

The pandemic impact

The effects of the pandemic on social capital in the GTA are uncertain at this time. Data is not being collected on this issue – at least not yet. But the pandemic may have made many of these disparities worse. Poverty may negatively impact social relationships through unemployment, downstream effects on mental health, the loss of family due to a common experience of disadvantage, and crises like eviction that strain people’s support networks.

In every case, these pressures may be getting worse for lower-income people in the GTA during the pandemic. If particular individuals with low income already had low access to social capital before the pandemic, then they may be struggling to maintain those connections now. During the vaccination rollout, vaccines were inequitably distributed in Ontario neighbourhoods, including by income and race. This is crucial for social capital since vaccines may aid in re-establishing social connections by facilitating in-person social interaction. Low-income, racialized communities may therefore see a downturn in their social capital following the pandemic.

A new normal for social capital

Fundamentally, “solving” our social capital deficits, and the damage they do, will require reducing various forms of structural inequality, including income inequality. But we can describe a better, but not perfect, social capital-equitable society.

Poverty does not have to mean low social capital, and if someone does have to live on a meager paycheque, it should not mean that they are reduced to a condition of having no social resources or support. A person living on a low income should have access to robust networks of support, through family, friends, and other social contacts, that all work to buffer them against the strains of poverty and give them a helping hand up the ladder of social mobility. It would mean that they have access to social spaces that allow them to meet and befriend people who assist them emotionally and instrumentally. It would also mean that when they do go to work, they are not prevented from making connections with anyone who is better-off than them; rather they are assisted by those who are in a more fortunate economic condition. Furthermore, it would mean living in an institutional context where crisis events, such as eviction, or a sudden loss, are manageable without having to exhaust oneself or one’s contacts to deal with it. It would in short be a society where people have more freedom than they do now – free to pursue the relationships that make them happier, healthier, and better-off.

What it would mean

The benefits of this shift would be felt throughout all reaches of the GTA. With access to supportive bonds, the region would very likely see an increase in people’s emotional and physical well-being, as their social needs were being met. Furthermore, economic mobility would be easier to achieve, since if there were more bonds of solidarity up and down the income ladder, then people with wealth would be more likely to lend a hand to those less well-off. The synergies that would emerge from this approach could even be mutually-reinforcing, setting us on a virtuous cycle where health, wealth, and connectedness would be more easily accessible for all individuals in the GTA.

Bringing this vision to fruition would not just mean greater economic mobility and well-being for individuals with low income. Bonds of friendship across social groups, including people with different levels of income, would help to create greater social cohesion and solidarity through the GTA as a whole. It would be easier to mobilize from the ground up, and potentially to focus on matters of policy and implementation of our values, rather than struggles between people jealously holding on to their resources, and those shut out of the halls of power. It could help us to imagine, discuss, and plan a GTA where everyone can reach their full potential, because we will have built lines of communication across our deepest social divides.

How we get there

Although this may seem like a far-off world, many social programs and institutions are already in the process of building social capital without knowing it. A daycare can create opportunities for parents to build social capital, just by being a shared space where people can meet other parents, and plan play dates, or access emotional support, or share helpful information. A graduate education program or employment program can build social capital among a cohort, simply by putting people with similar interests in routine contact with one another, so that when one member of the cohort needs support, there may be someone at-hand they can turn to. New community gardens or dog parks could be similar spaces, where people regularly come together to form bonds by conversing over a common topic (i.e. gardening, or their pets). We should start to create social capital consciously and equitably, by recognizing and building upon the strengths that we already have.

Here are just a few examples of places we can start:

- Organizations likely relevant to or who are likely candidates to build social capital could make it part of a person’s job description to help build social capital, or create new positions where it is a person’s primary responsibility. An example of this may be lay community health workers, whose role is to create and maintain bridges between formal health organizations and a wider community of potential service-users. Similar roles could be considered for early childhood education centres (which could undertake to bring their community together) schools (which could work with, and better connect, parents), or even large businesses (which are in some ways communities of their own, where Torontonians may spend more waking hours than they do in their neighbourhoods). Entire organizations could also be founded to serve this purpose, sometimes called ‘community backbone organizations.’ To support this work, best practices should be developed.

- Workplaces could move beyond hiring practices, targets, or quotas to systems of sponsorship, where managers are evaluated by their ability to move lower-income workers into positions of greater responsibility and higher pay. They could also support democratized workplace structures such as cross-training and self-directed teams, where people work together across hierarchies, building bonds of solidarity.

- Governments must maintain and expand social safety nets, since crisis can undermine a person’s social capital. Unemployment, homelessness, well-being, and health crises (including both mental and physical health) all need strong supports to ensure the strength of a person’s social capital.

- Create cross-sectoral projects that support people at crucial times for the formation of their social capital, for instance, in periods of emerging adulthood in educational institutions (i.e. high school and post-secondary education).

- Finally, civil society and government should come together with supporting social capital as a goal. We know social capital’s negative effects for health and economic mobility and security – it is time to address it through new ideas and new research into solutions. This work should lead to municipal, provincial, and federal levels of government being able to propose and implement long-term plans, with measurable targets, to improve social capital.

One of the obstacles to building social capital is refusal, or hesitancy, to imagine these interventions as possibilities. Building social capital requires creating the conditions for people to do something that they do spontaneously: help one another. The changes that we need to make are substantial, but the rewards are profound. What we will gain is a fuller expression of our best natures and a social fabric made strong by a foundation in equity.