The TTC has committed to making transit more efficient. But making public transit better is about more than just quicker service – it’s about protecting our health. We need a public transit system that works for public health. For the TTC to build an equitable and healthy transit system, it should begin by:

Putting riders first. Bus systems between the city and the outer suburbs should be coordinated and connected for riders who make multiple transfers. Extended operating hours are also critical for workers who work early morning or late night hours.

Inclusive planning processes. Marginalized individuals have been cut out of transit planning and as a result public transit does not meet their diverse needs. Through more inclusive planning, Toronto’s public transit system can advance health equity.

On average, there are 1.7 million riders on the TTC each day. However, not all riders experience public transit equally. Connected and reliable public transportation can provide access to job and education opportunities, support upward mobility and promote social inclusion. It also plays a key role in supporting vulnerable populations.

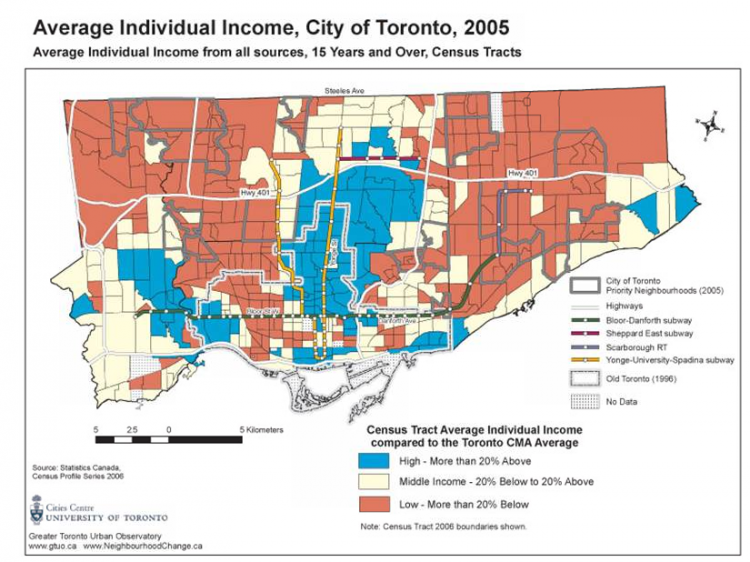

Toronto’s changing demographics mean that those who rely on public transit the most are no longer living downtown. Toronto is becoming less affordable and low-income populations are increasingly moving out of the downtown core to spatially segregated neighbourhoods with limited public transit infrastructure.

Residents living in these neighbourhoods are not only more likely to live on lower incomes, but they are less likely to have cars and are more likely to depend on public transit for daily activities such as getting to and from work, buying groceries, visiting family and friends and accessing services.

Figure 1. Average Individual Income, City of Toronto, 2005.

Proximity to public transportation is an important indicator of health and well-being because services are still largely concentrated in the city core. However, studies show that the people who rely on public transit most have significantly decreased transit scores, making it difficult to access the services they need.

In fact, of Canada’s three biggest Census Metropolitan Areas, Toronto has the longest commuting rate, with 34 per cent of riders commuting for more than 2 hours every day. These commuters are also serviced by buses which are generally less connected, experience more delays and run less frequently than subways or streetcars.

Individuals who experience long commutes not only suffer a loss of time, they also potentially lose out on a lot more – including their ability to pursue education, healthcare services, and employment. Our transit system has failed to keep up with the needs of GTA residents and as a result is making some of us sick.

So, who does this affect?

Research tells us that it is marginalized groups including women, those living in poverty, and racialized individuals who are more likely to live in areas with limited transit infrastructure and as a result endure longer commutes.

Unreliable, infrequent and poorly timed public transit can also isolate already vulnerable people. Poor public transit means people are not only less connected to friends and family – but also to the wider community, potentially missing out on other opportunities for social connection. Studies show that infrequent participation in social activities can lead to feelings of loneliness, lower levels of self-rated physical health and can result in higher rates of morbidity and mortality.

The TTC should do more to protect our health. However, they cannot do it alone. The subsidy the TTC receives from government needs to be predictable and enough to support the growing city. According to the TTC budget, in 2010 the subsidy they received from government was $0.93 per rider. Since then, the subsidy has fluctuated significantly, even dropping as low as $0.78 in 2013. In 2018, however, the subsidy grew to $1.08 per rider. This increase brings the TTC closer to a budget they can operate on, however still falls short of many other cities in North America.

Creating a coordinated public transit system will not only help riders get to their destinations faster and efficiently but it will help ensure that all individuals are able to fully participate in their communities.

For the TTC to truly be the better way, it must be more responsive to the needs of all people – especially the most vulnerable.